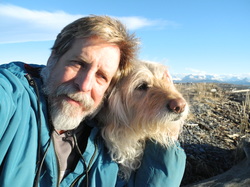

Michael A Armstrong

Michael A Armstrong Alaska almost qualifies as a science fiction destination: There are landscapes that look like moonscapes, weather that reaches the far end of human capacity to endure, and men and women who have learned to survive--and flourish--under all kinds of challenging conditions. So how does Alaska affect the work of a science fiction writer who has made his life here? Today’s conversation is with MICHAEL A ARMSTRONG, author of the novel BRIDGE OVER HELL and other science fiction writings.

Michael, decades ago you and I were both enrolled in the MFA program at the University of Alaska, Anchorage. I recall you teaching an undergraduate seminar in science fiction with William Gibson’s Neuromancer as a text. These many years later, you’re still writing science fiction, but your life path has gone in other directions too. Tell us about your writing career.

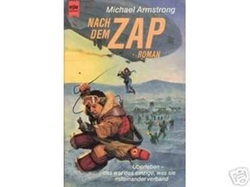

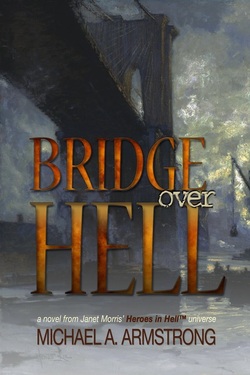

Shortly after getting my MFA, I sold my thesis novel, "PRAK" (for People's Republic of Alaska) to Warner Books; it was later published as "After the Zap." "Bridge Over Hell" actually was my second novel written. While working on my MFA, I sold a short story, "Going After Arviq," to Janet Morris, a writer and editor, for her anthology, "Afterwar." Janet also had started a fantasy shared-world series, Heroes in Hell, set in the classical hell. She asked me to write several stories for that anthology series. One of them, "Madly Meeting Logically," with the poet Hart Crane as its hero, became "Bridge Over Hell." I signed a contract with Baen Books, the publisher then of the Heroes in Hell series, to write "Bridge Over Hell."

However, when I delivered the final draft, Baen had run into some cash flow problems and kept delaying payment on the last third of the advance. Rather than pay me for an accepted manuscript, Jim Baen, the owner, went back on his word and rejected the novel. I kept the initial two-thirds of the advance (which was more than I got paid for "After the Zap") and the rights. A few years ago when Janet revived the Heroes in Hell series through her own small-press publisher, Perseid, she agreed to resurrect "Bridge Over Hell." So, 25 years after I wrote the novel, it saw print. I've also done more Heroes in Hell stories, for "Lawyers in Hell" (about Richard Nixon representing the Scottish Borders reiver, Kinmont Willie Armstrong), "Rogues in Hell" (which has the original Hart Crane story that was never published), and more recently, "Poets in Hell."

My fourth novel is "The Hidden War," the science fiction space novel I always wanted to write as a boy. It's classic science fiction, supposedly about alien invaders and brave defenders of human civilization, except that its hero has grown up on an asteroid colony whose culture is based on the Beat Generation of the late 1950s and early 1960s. When I wrote the novel, I'd read Allen Ginsberg to get into the proper groove. The late Brian Thomsen, who was my editor for "After the Zap" and "Agviq," bought "The Hidden War" when he moved from Warner Books to TSR Books.

I'm now trying to sell "Truck Stop Earth," a novel set in Alaska about a guy who truly believes he has been abducted by aliens. I wrote that one after a critic who reviewed "The Hidden War" said it wasn't as wonky as "After the Zap." "You want wonky," I thought, "I'll show you wonky." "Truck Stop Earth" is fighting a tortured path toward publication. My elevator pitch for it is "Holden Caulfield with aliens."

That's sort of the story of my writing career. I've been publishing since 1980, when my first story saw print in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. I've lost count of how many short stories I've published, but it's in the dozens. I've been writing seriously longer than that, since 1975, when I attended the Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop. I write in fits and starts, publish in fits and starts, and write because that's what I do.

The challenge for any writer not lucky enough or persistent enough or whatever enough to make a career solely from his or her art is to make a living in some other ways. After I got my MFA, I worked 13 years teaching as an adjunct instructor at UAA, first while living in Anchorage and later after moving to Homer, mainly through the distance education program. The idea of working as an adjunct is to gain experience to get a full-time teaching job. I realized early on that to get a tenured position I might have to move outside of Alaska, and I don't want to do that. Alaska is my home. To get hired as a professor means sucking up to a lot of academics. Academic culture is ruthless and petty, and I'm not good at sucking up to people. Alaska also has an inferiority complex. In academia and other fields, if you got your degree or experience in Alaska, you can't be any good, but if you taught at a cow college in the Midwest, you're a genius. That's changing, but not fast enough.

The University of Alaska balances its budget on the backs of adjunct instructors, and to its shame does not adequately compensate them for the work they do. I calculated once that the first 10 students in my class paid my salary and the next 15 students worth of tuition were profit for the university. I quit teaching as an adjunct after I helped organize United Academic Adjuncts. Shortly after that for some reason UAA quit offering me teaching contracts.

That didn't matter. In 1999 I started working for the Homer News, at which I make a modest living, with benefits like health insurance. (I realized the importance of that last May when I went into cardiac arrest and had to be medvaced to Anchorage, which is how I wound up with a pacemaker.) The important thing about being a reporter is that I get paid for telling stories, which is really what I like to do. The stories I tell happen to be true. I meet a lot of interesting people and learn a lot. At a weekly newspaper, a reporter by necessity must be a generalist, quick to learn about hundreds of topics. Last week I had to learn about Alaska petroleum tax policy and West African music and culture. As Robert Heinlein said, "Specialization is for insects."

There are so many subgenres in science fiction. I found a partial list that describes hard science fiction, soft and social science fiction, cyberpunk, time travel, alternate history, military science fiction, superhuman, apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic, space opera, space frontier and space western. How do you categorize your books?

The convenient labels are science fiction or fantasy. "Bridge Over Hell" is fantasy. Most everything else is science fiction. I've written post-apocalyptic fiction, hard and soft sf, social sf and even cyberpunk. With "After the Zap" I tried to start the genre of Bush Punk, but it didn't take. Science fiction is a wide genre with many edges that defies definition and categorization. I like Darko Suvin's idea of sf as exploring the concept of estrangement. One of the more useful suggestions is that of Fred Pohl, who said "science fiction explores the futures we are making to see if we want to live there."

There's also an irony to sf. For all these years we wrote about societies in which science and technology changed quickly and had a major impact on our culture, and here we are, living in that future. In some ways to write science fiction is to write about the modern world. I think the difference is a matter of tone.

Is there a community of science fiction writers in Alaska?

I've been a member of the Science-fiction and Fantasy Writers of America since 1981 and served as Western Regional Director from 1996-99. Alaska has as many SFWA members as Delaware and Louisiana, so we're in good shape. Dana Stabenow, the mystery writer who got her start in science fiction, lives a few miles from me in Homer. The rest live in Fairbanks and Dillingham. We keep in touch mostly through Facebook and online. Sometimes, but only rarely, we'll get together at conferences. Other Alaska sf and fantasy writers are George Guthridge, Elyse Guttenberg, Terry Boren and David Marusek.

Has living in Alaska most of your adult life colored your writing? Although you don’t site your books in Alaska, I’m guessing you have had experiences that flow into your writing, either into your plots or into your characters.

Actually, "After the Zap," "Agviq," and "Truck Stop Earth" are all set in Alaska. I grew up in Florida but have lived here since 1979, more than half my life. (I was born in 1956.) Many of my short stories also are set in Alaska, such as "The Duh Vice" and "Old One Antler." The struggle for survival, a common Alaska theme, gets used in some of my deep-space stories.

I based the idea of one story, "Catch the Wotan!", about a man adrift in space, on the idea of being adrift at sea in a survival suit. Another space short story, "The Deadliest Moop," can essentially be described as "crab fishermen in space." (They're hunting for moop, material out of place, detritus from exploded satellites and other space junk.) "Agviq" came out of summers working on archaeological digs in the arctic. The story of Alaska is about struggling against a harsh and dangerous environment. That theme gets reflected often in my work.

Writers write for all sorts of reasons, but most yearn for publication. Do you think it’s more difficult to sell and market your science fiction books from Alaska than it would be from urban centers Outside, where agents, publishers and booksellers have more of a physical presence? Or does the existence of the Internet negate the effects of geographical boundaries?

It would probably be easier to sell my work if I made periodic trips to New York. The value of networking cannot be underestimated. I've mostly worked with agents, at least on my books, which made selling them easier. However, when I've tried to sell books cold, I've discovered agents often don't want to work that hard and can be pretty useless in many ways. Science fiction and fantasy publishing deals often get made at conventions and conferences like the Worldcons or World Fantasy Con. I don't go to those too much. I do maintain online contacts with many writers, agents, and editors, a practice that goes back way before Facebook to GEnie, an early online community of the 1990s. The Internet, if properly used, negates many of the geographic limitations of Alaska.

Alaska does have an advantage in that many people think of it as exotic and mysterious and want to know more about our state and its people. Works set in Alaska still have a bit of an edge over, say, Kansas.

Are you working on a new book now?

I'm always working on a new book. The book on my front burner is "Borderers," a fantasy novel that's really a science fiction novel. I follow the advice of one of my Clarion teachers, Kate Wilhelm, who said, "Don't talk too much about your writing until it's done. It sucks the life out of it." Borderers is set in the fictional Alaska town of Della, a stand-in for Homer, which also was the setting for "Truck Stop Earth."

What are some of your favorite books and authors?

I learned to write sf novels by reading Phillip K. Dick. I'm especially fond of his "The Man in the High Castle." His use of the I Ching inspired me in "After the Zap." As a teenager, I read voraciously in sf. Harlan Ellison, Robert Silverberg, Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein — all the great masters, I've read them. I studied with Joe Haldeman, Samuel R. Delany, Gene Wolfe, Robert Zelazny, Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm, and consider them all major influences. I'm fond of the modernist and Beat poets, but I don't read as much modern poetry as I should. I also don't read much modern sf. William Gibson still impresses me — I think he's the very model of a modern sf writer. I really like Cory Doctorow's young adult novels, "Little Brother" and "Homeland."

I don't read much fantasy, especially high fantasy. My response to fantasy was a young adult novel I never finished, but may someday, an anarchist fantasy called "Sam The Thumbless." I might be the only sf writer never to have read J.R.R. Tolkien. I made a vain effort to read The Lord of the Rings trilogy, but stopped 100 pages in when I realized Bilbo et al. still frigging hadn't left the Shire.

Outside of sf, I read thrillers and mysteries: Michael Connelly, Ian Rankin, Martin Cruz Smith. I regularly raid the advance reading copy pile at my wife's bookstore. (Jenny is a partner at the Homer Bookstore.) I'll pick up anything that looks fun. I just read John Straley's "Cold Storage, Alaska," a fine and quirky mystery novel. I should read more general fiction, but not as much as I should. That's why I wound up in a degree in humanities from New College of Florida, and not, as would be expected, a degree in literature. I would get distracted from the core reading list and go off and explore things like Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley or the late 19th century romantic fantasists.

After the Zap, Agviq, and the Hidden War are available as ebooks from iBooks, Nook, and Amazon Kindle, and from Kobo through the Homer Bookstore (www.homerbookstore.com) or the Kobo Books website. Bridge Over Hell is available as an ebook or paper edition from Nook or Amazon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed