The photograph in the marketing material for the class hooked me: a lineup of gleaming tiny glass goblets, each delicate and unique, some with swaying stems.

Glass. There is something magical about glass. It’s a lovely material. I’ve been working in clay for years now, but clay, after all, is just mud. You can make something wonderful with it, but the big lumpy bags that await you in the studio are just heavy hunks of earth. But glass promises beauty from its very beginning.

So I made the jump and enrolled in the weekend flameworking introductory workshop, two days of 9-to-5 working with borosilicate glass at a local art school.

I didn’t know anything about flameworking. I know enough about glassblowing to know that it isn’t for me. I tried glassblowing once, for an afternoon, and it was like spending time in hell. The workspace was horrendously hot, the air scorched by the open fiery furnaces flowing with molten glass, glowing the brilliant orange of a volcanic eruption. The metal pipes that glassblowers use to gather the molten material from the furnaces are heavy and awkward. To collect the glass, you must get very close to the open maw of the furnace, so close that your fingers feel like they’re burning. The process isn’t comfortable or measured; once you begin, you fight against the clock to form your piece before it hardens. I know there are women glassblowers, many more these days, but historically this has been a very male-dominated, macho business, and it feels that way.

Flameworking (also called lampworking) suggested a gentler approach to glass.

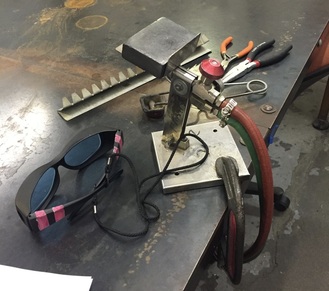

There were four of us in the class: two young men who looked like high school students, a young woman in her thirties, and me. The other three had previous glass experience, so I was the only newbie. We were issued our tools and directed to set up our stations. We clamped our propane torches onto the metal table and immediately I had misgivings. It wasn’t an open furnace, but it was FIRE—fire that spurted freely from the torch in an impressive tapered blue flame. The list of cautionary “don’t” didn’t help: Never reach through your torch flame, wear your didymium glasses whenever anyone at the table was working with glass to protect your eyes from explosions, always turn on the propane knob on the torch before turning on the oxygen, always pick up your glasswork with pliers because you can’t visually distinguish the hot glass from the cold, spin your glass continuously to make sure the heat is evenly distributed on its surface. So many ways to screw up.

At this point, honestly, my instinct was to cut and run. I absolutely cringed when I lit my torch, but I stayed.

Cheryl, our instructor, walked us through our first project: icicles. We heated our glass rods with our propane torches until they were pliable, and then twisted them into coiled shapes, finishing by pulling off one end and fashioning a hook. Sounds simple, doesn’t it? Well, it wasn’t. The glass cools quickly and becomes immobile, so heating a baton-shaped hunk of glass and twisting it evenly is a feat in itself. And the hook…slowly disengage from one end of your icicle, gracefully and slowly pulling the end of your pontil in a slow circle to form a loop, while the glass cools and hardens. My icicle looked like I’d strangled it. Cheryl, in her oh-so-kind instructor voice, told me that some people like that look, because it reminds them of vintage distressed glass. Right.

On top of the physical scariness of the whole process, a whole new vocabulary was in play: annealing, coefficient of thermal expansion, compatibility of glasses, frit, gathering, maria (not part of a prayer, but rather the blob that’s formed when you push two hot glass rods or tubes together), pontil, punt, strain point, stringers…my brain was in full-on overdrive.

There was so much to learn. The torch heat had to be modulated depending upon the part of the process you were engaged in; the rods had to be positioned in, out, above or below the flame depending upon the heat of the glass and what you were doing.

The icicle was only the first project, and all I could focus on was that I was going to set my hair on fire.

In short order, we attempted other projects. We melted, we pulled, we smashed glass. We pressed molten glass into simple pendants, we applied colors to clear rods and created glass seaweed, and we cut and pulled hot colored glass with needle pliers to form starfish. My starfish was a big red blob. Cheryl, still carefully positive, suggested that I start again. We made marbles, which sounds SO SIMPLE but was painfully tedious. (At least now I know how those patterns inside the marbles are made.) At the end of the first day, I was beyond exhausted.

We started the second day with coral sculptures. Mine emerged looking like the wooden terrace you’d use to tack up your tomato plants. To add a little more terror to my experience, in addition to the fixed flaming propane torch, I was now issued a small hand held propane torch for the smaller connections. Now I had to contend with two flames. Every time I tried to soften the look of my poor stick-like coral, I managed to melt away its legs. I failed coral.

.

Now, Cheryl said, we were going to progress to more difficult work. (!) We were issued rubber tubing and hollow glass rods. We were going to blow hollow tree ornaments. She demonstrated the process which involved about 20 delicate and skilled steps. The three other students grabbed their materials and tubing and headed back to their stations with determined enthusiasm.

It was beyond me and I knew it. When I asked Cheryl if I could practice some of the earlier work, she nodded. Maybe you’d like to make more icicles, she suggested.

So, after I slinked away at the end of the second day, I reflected on the experience. Despite my abysmal performance, I learned so much about flameworking and the properties of glass. I had been terrified by my propane-fueled flame and yet I hadn’t set myself on fire or burned myself too badly. (I did scorch a few fingers by touching hot glass. It was hard to remember all the rules.) My brain had been fully engaged and challenged for two days and was absolutely fried, but a heavy-duty brain workout isn’t a terrible thing.

I did realize, however, that I’m not very good at being a beginner.

Here’s my takeaway: When we were younger, we expected to be clumsy and unschooled when we tried something new. We accepted our role as students, as humble bumblers. We understood that a new skill required time fumbling and making mistakes. But now, I think our experience as competent adults can work against us. Our adult confidence makes us feel like we have to be good at what we do, even if it’s something new. We’re not willing to stumble, to struggle, to look stupid. We don’t want to look foolish. We want to be an expert from the get-go.

When I was in class, I kept asking myself, why aren’t I better at this? But now that I’ve stepped away and looked back, the answer is simple. It’s hard, and it’s a skill, and I just picked this up for the first time. It’s all new for me, from lighting the propane torch to learning the names of the tools to absorbing the feel of the molten glass, knowing when to heat it and when to pull it and when to stop.

So if there was a lesson for me this week, it wasn’t about the acquisition of skills of flameworking molten glass. Right now, I suck at that. The lesson for me is that as I go forward, as I try new things, I’m probably going to suck at a lot of things, at first. But it’s the price of going forward.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed